I’ve been working sporadically on a series of what I call “cover pics,” which are basically the visual art equivalent of cover tracks by musicians who replay popular songs that were first written and performed by other musicians. (The most relevant to this current post is Studies of da Vinci’s Studies of the Fetus…) For that cover pic I used information and images found here, at The Royal Collection Trust.

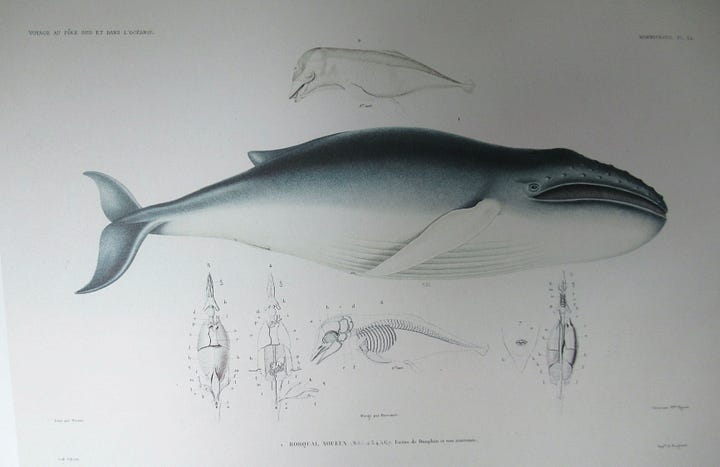

For this post, I’ve used a reprint of a plate originally published in an anthology of Zoology compiled by J.Dumont D’Urville. In volume 3, artwork by naturalist Jean-Charles Werner is included in “Voyage au Pole Sud et dans L’Oceanie sur les Corvettes l’Astrolab et la Zelle” (Voyage to the South Pole and Oceania on the Corvettes Astrolab and Zelle), published sometime between 1846 and 1853.

I want to refer to the writing and images in the margins of the original work, so I’ve included a photo of the reprint: because who has time and funding to traipse all the way over to the Central Library of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, France? This is what the internet is good for, as long as we cite the original human content creators, fair and square.

Speaking of which: two artists are credited with the illustration. A person named “Egasse” (with 99% certainty, a woman, btw., referred to in some sources as “MMe/Ms Egasse”) created the engraving used to reproduce the painting originally done by Werner. Whether both artists were aboard the expeditions made by “Astrolab” and “Zelle” I do not know, but just for the record, aren’t those cool names for 19th century cruise ships?

Anyhow, back to the whales.

Now that the unholy alliance between political messaging and medical treatment that battered much of the western world for several years has begun selling indulgences to the likes of Mark Zuckerberg — and platforms like his have been freed of their “fact-checkers” — the algorithm has started serving me lots of odd cooking videos. And occasionally some truly good photography.

Most recently, a photo showing how whales sleep taken by Stephane Granzotto, popped up on my facebook feed. The discovery of the fact that they hang vertically, like pupae under the ocean’s surface, is credited to his photography. Fascinating.

Now, on to the fine print on my reference image: The top left states the name of the expedition, the top right tells us that it is plate 24 in the book, and the bottom right tells us it was printed by a company owned by the Bougeard family. Underneath the whale are a series of small anatomical drawings depicting a skeleton and internal organs.

Let’s please keep in mind that the daguerrotype first came on the scene in 1835 and the process needed a lot of refining before it would reach the stage where anything was portable. So recording the natural world out on the windy wavy ocean was all about drawing skills. Really, really good drawing skills. Add to that the fact that diving suits and helmets and underwater breathing technology were all rudimentary at best. You really had to use your imagination to see the way things actually were.

The only way to record internal organs and structure was through dissection or having the incredible luck to find an assemblage of bones in an order approximating the original skeleton and innards of a creature. And now we get to the heart of the matter: The text underneath the whale says “1. Rorqual Noueux. (Nob.) 2,3,4,6,7. Foetus der Dauphin et son anatomie.”

I don’t know what “Nob.” means and Google Translate is not much help with translations of abbreviations from 19th century French, because AI still can’t know the truth about things before it was born. Even now, I want to point, out:

This is why I have no fear of AI taking all our jobs. (Try to reverse-engineer that and google “Knotty Rorqual” — internet intelligence agents return the answer that there is no such thing.)

In the original drawing by MMe Egasse, the small figures surrounding the whale are labelled as “Dolphin Fetus and its anatomy.”

Unless they were severely short of paper, and had to cram a lot of drawings of unrelated species onto one sheet, it really looks like it could just be possible… (Could it be possible?)… that people several centuries ago, who had absolutely no way of knowing how whales sleep, also thought, (just possibly thought), that dolphins might be baby whales? It’s not completely out of the question, particularly because at that time, free-diving and diving bells had been around for centuries, allowing people to freely explore the underwater world close to shore. Or, perhaps, being the woman disguised as a draftsman that she was, Mme Egasse was having a laugh.

Naturalists would be very familiar with the tendency of tropical fish in that region (called, at the time, “Oceania”) to look completely different in their juvenile incarnation, and to change both color and form as they became adults. Possibly these two drawings were made from carcasses serendipitiously somehow discovered near each other. If a pregnant dolphin had been caught, killed and dissected, one would think the adult would have been pictured on the same page as the fetus. Ditto for any variant of Rorqual whale. I wouldn’t even begin to know how to figure out when people in France discovered that whales and dolphins are mammals. And it’s a subject far outside the bounds, and above the pay grade, of this little post.

Science is a process of discovery. A process. History always shows us that. But for non-history buffs? Science still doesn’t know as much as we think it does, at least not with any certainty. That has been made very, very clear in the past few years.

And some of us are just not going to stop talking about it. We can do that because we have nothing to fear. We’ve already lost our jobs, our status, many of our friends and with all that our place in the reigning technocracy. Was it Joni Mitchel who first sang “Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose”?

Here comes my segue into something the reader might (or might not) find to be wholly unrelated.

Some of us are not going to stop talking about what “The Science” doesn’t really know because it’s potentially important for the future of our humanity. I know this because three years ago, at around this time of year, in the middle of deep, cold winter — I was sitting in the waiting room of a hospital and the woman sitting across from me with her husband told me she was there for a procedure called “dilation and curettage.” Which, to put it crassly, is the scraping out of everything in a woman’s womb. Her husband looked devastated.

She had to have this medical procedure because she had been carrying twin baby boys when her employer, a janitorial company, forced her to get a Covid vaccination.

Within days, the hearts of both those baby boys stopped beating. She had become a walking tomb.